Introduction

In this fourth blog post, I want to explore the subject of incumbency.

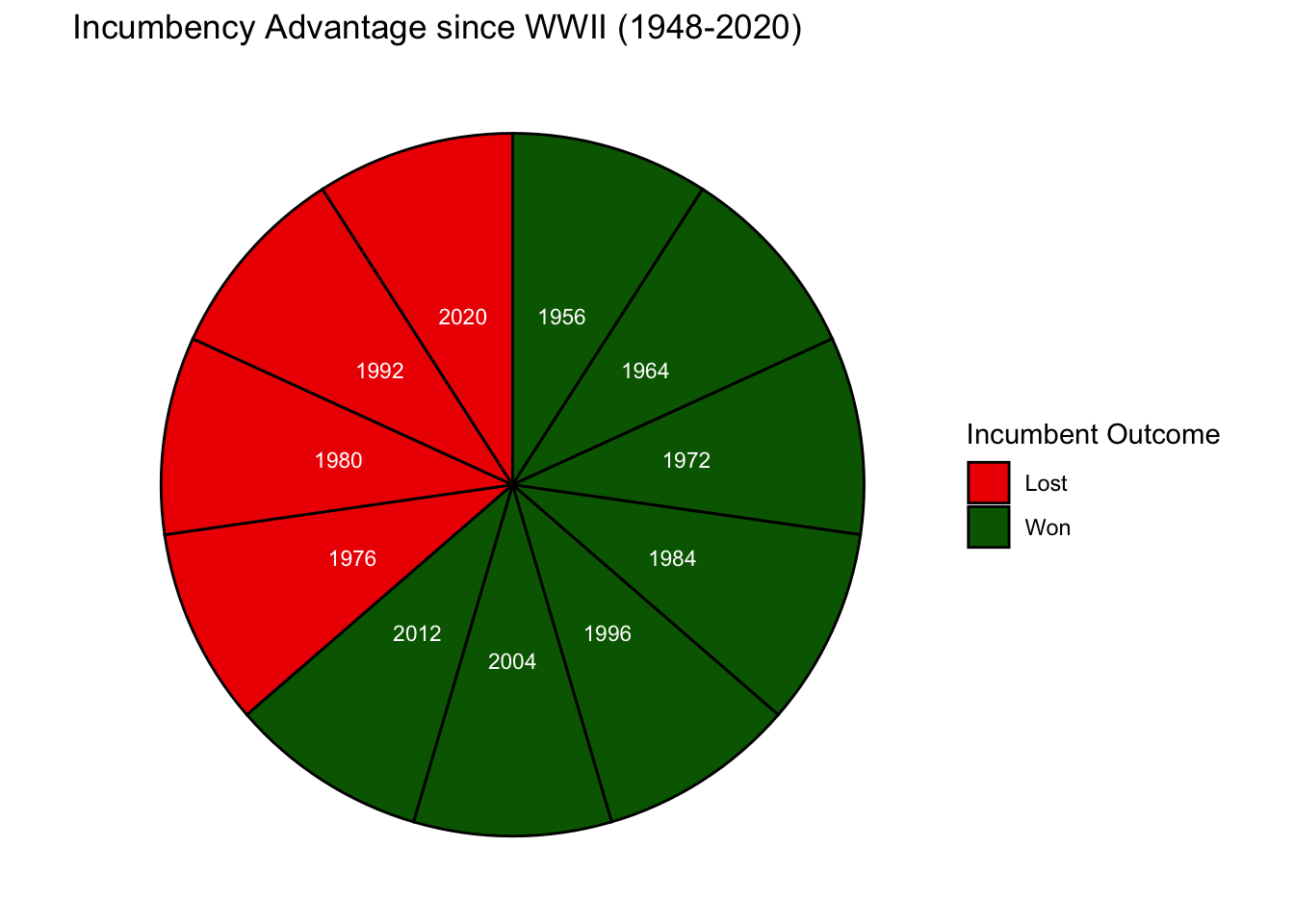

In the 11 presidential elections since 1948 in which the incumbent president was running, the incumbent’s bid was successful 7 times. As a percentage, this is roughly 64% of the time.

Political pundits have long identified this apparent benefit of currently holding the political office for which one is running as incumbency advantage.

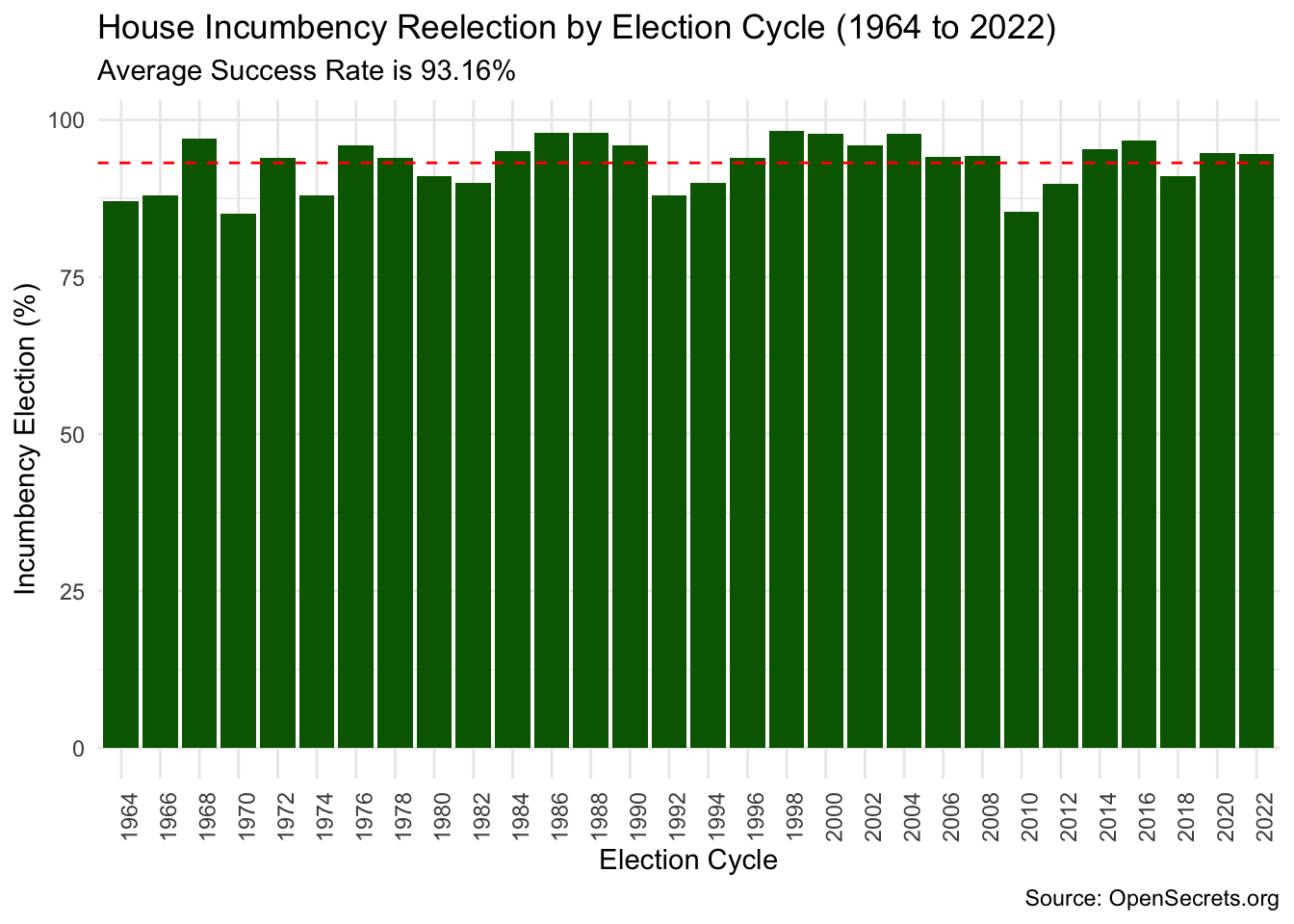

One need only take a look at the House reelection rates among incumbent candidates to see clear evidence of this advantage.

Between 1964 and 2022, on average, incumbent candidates running for the House of Representatives won their election 93.16% of the time (OpenSecrets). While this percentage is not wholly attributable to incumbency advantage since most House elections occur in non-competitive congressional districts, this 93% figure still conveys the political edge that incumbency affords political candidates.

Many have hypothesized that incumbency advantage is largely the product of incumbent candidates’ name-recognition, previous experience campaigning and fundraising, and their ability to take credit for economic gains over the last 4 years. It is this last element of incumbency advantage, also known as pork, that I want to focus my blog on.

The code used to produce these visualizations is publicly available in my github repository and draws heavily from the section notes and sample code provided by the Gov 1347 Head Teaching Fellow, Matthew Dardet.

Analysis

The term, “pork,” was first used to reference questionably appropriated public spending in the 19th-century by American author Edward Everett Hale in his 1863 short story, “The Children of the Public.” Contained within his larger book. The Man Without a Country, “The Children of the Public” uses the imagery of pork barrels to suggest wasteful spending. At a time when refrigerators were not yet invented, pork would be salted and stored in large, wooden barrels. These wooden barrels were quite valuable. Hence, “pork barrel spending” is like taking a cut from this larger pool of resources. Examples of “pork” include earmarked investments in unimportant projects that go toward specific states or constituents, often to gain their favor or reward them for their support.

The theory of pork in the context of incumbency advantage is that presidential candidates can propose budgets and lead initiatives that will direct federal funding to more competitive states that they want to win in the next election cycle.

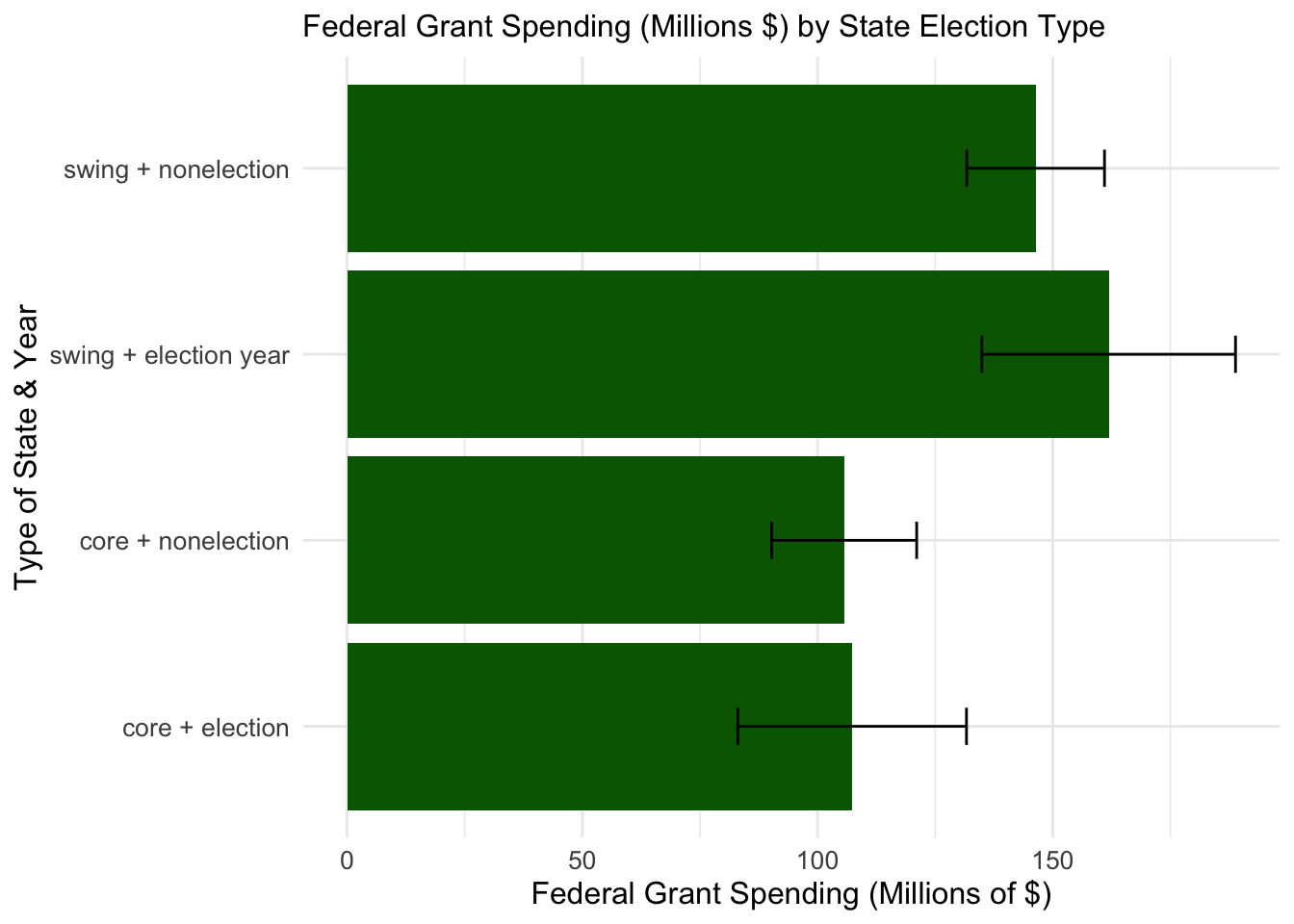

To test this, I will first visualize federal grant spending in millions of dollars by states to see if competitive states receive more money than non-competitive states, on average. I will do this by using a 1984-2008 federal grants data set harmonized by Douglas Kriner and Andrew Reeves as part of their 2015 paper, “Presidential Particularism and Divide-the-Dollar Politics.”

As is visible, swing states appear to have historically received more federal grant funding than non-swing states. While not statistically significant, it is plausible that, even within swing states, more federal funding is received during election years than non-election years.

To further test this pork theory, I will run a regression at the county level. I am interested in determining whether there is a statistically significant relationship between incumbent vote swing and federal grant spending and if this relationship differs for districts in competitive and non-competitive states. A state will be considered competitive if the losing candidate averaged at least 45% in the last three presidential elections.

$$ IncVoteSwing_t = \beta_0 + \beta_1(\Delta FedGrantSpend_t \text{ x }CompetitiveState_t) + $$ $$ \beta_2\Delta FedGrantSpend + \beta_3CompetitiveState_t + $$ $$ \beta_t \text{(Year Fixed Effects)} + \delta_t \text{(Additional Controls)} $$I will also control for additional variables like Iraq war casualties, % change in county-level per capita income, and ad spending to mitigate omitted variable bias.

| Dependent variable: | |

| Incumbent Vote Swing | |

| Federal Grants (%) | 0.004*** |

| (0.001) | |

| Competitive State | 0.155* |

| (0.077) | |

| Federal Grants * Competitive State | 0.006*** |

| (0.002) | |

| Constant | -6.523*** |

| (0.085) | |

| Observations | 17,959 |

| R2 | 0.420 |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.419 |

| Note: | *p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001 |

| Standard errors are in parentheses. | |

After controlling for potential confounders, running the regression, and outputting the variables of interest, we can note the following:

An additional percentage point increase in federal grants translates to a small but statistically significant increase in incumbent vote swing on average.

Counties in competitive states tend to contribute 0.155 more percentage points to incumbent vote swing than those in non-competitive states.

The effect of federal grant spending on incumbent vote swing is greater in competitive states.

All of these main coefficients of interest are statistically significant, and we can conclude that federal grant spending, does have a significant effect on incumbent vote share, and that it is greater in swing states. This would help explain why pork seems to go disproportionately to swing states.

Incumbency in 2024

Now that we have established the relevancy of incumbency in the context of presidential elections, it is natural to consider the role that incumbency advantage will play in an election year as unprecedented as 2024.

This election cycle is particularly distinct in that neither Trump nor Harris fits the usual profile of an “incumbent” — neither was the president in the term immediately previous this upcoming election. Biden was. However, it is arguable that both, also, could be considered incumbent to some extent — Trump, because he has served as president once before, and, Harris, because she was Vice President under Joe Biden.

My personal perspective is that Harris could be described as the “incumbent” candidate more accurately than Trump. Her name was on Biden’s 2024 ticket and she was a highly visible presence on the campaign trail. While neither Harris nor Trump lack name recognition, Harris has full access to Biden’s campaign funds since they ran on the same ticket, and she benefits from all the same network and “pork” advantages that a typical incumbent would. Both Trump and Harris also experienced relative ease in securing their respective party nominations, an advantage incumbents’ usually possess.

Allan Lichtman, an American University professor who specializes in modern American history and political science, has accurately predicted 9 out of the 10 past presidential elections using a “13 key guide.” This guide relies heavily on incumbent party advantage, something Harris possesses that Trump does not. In this way, she stands to gain more from incumbency advantage than Trump despite not having been president before, herself. Lichtman has also predicted a Harris win, Kamala securing 8 of the 11 keys on which Lichtman took a position (Padilla 2024).

Citations:

Hale, Edward Everett, et al. The Man without a Country. Little, Brown, and Company, 1898.

Kriner, Douglas L., and Andrew Reeves “Presidential Particularism and Divide-the-Dollar Politics.” American Political Science Review 109.1 (2015): 155–171. Web.

Padilla, Ramon. “Historian’s Election Prediction System Is (Almost) Always Correct. Here’s How It Works.” USA Today, Gannett Satellite Information Network, 29 Sept. 2024, www.usatoday.com/story/graphics/2024/09/29/allan-lichtman-election-prediction-system-explained/75352476007/.

“Reelection Rates over the Years.” OpenSecrets, www.opensecrets.org/elections-overview/reelection-rates. Accessed 28 Sept. 2024.

Data Sources:

Data are from the US presidential election popular vote results from 1948-2020 and Kriner and Reeves 2015.